Editor’s Note: The following is rather lengthy. If you want to jump straight to where the DPA knowingly filed an incorrect quarterly report, click here. If you want to see where the investigators’ report was incorrect about Karyn Bradford-Coleman’s raises, click here. If you want to read about how the report shows that Bradford-Coleman’s notarization of certain reports was improper, click here. And if you want to see visual proof that Michael John Gray lied about being in the room when some reports were notarized, click here.

This coming Saturday (August 31), the Democratic Party of Arkansas is having a meeting of its Executive Committee to discuss two grievances (here and here) filed against the party by the party’s former attorney. That being the case, this seems like as good of a time as any to review the report they released at their prior meeting on August 17 as well as the video of that meeting, just so everyone is on the same page about the half-truths and outright lies the party has been peddling for the past few weeks.

As you may recall, on August 17, the DPA had a special meeting of the Executive Committee1 and the State Committee. During the State Committee meeting, the DPA presented those in attendance with a report authored by the law firm of Shults & Adams. If we are being charitable, the report–and the presentation of it–was a misleading dog-and-pony show.2 Let’s tackle the report (and accompanying video) in the same order it was presented. As we go through the report and video in this post, we will divvy it up by page number; any time stamps listed below refer to the video of the meeting, which you can view here:

Page 1

During the meeting, Annie Depper stated (15:28) that DPA “signed a letter of representation” with Shults & Adams on Monday, August 12. The report states that DPA “engaged the law firm” on that date.

It’s possible that this is just sloppy phrasing. However, if the statements are accurate, the idea of full transparency in the reporting is out the window from the start; by signing a letter of representation, DPA became a client of Shults & Adams, meaning that, in theory, DPA (as the client) could prevent the firm from releasing any information that DPA considered confidential. (The letter of representation was not included with the report or otherwise provided in a way that would allow anyone to see the scope of the attorney-client relationship at play here.)3

The report states that the firm was asked “to investigate, to the extent feasible in a few days.” Depper explained (starting at 14:20) that DPA “knew the investigation had to be done quickly.” Why? There was literally nothing requiring that the investigation be completed by the date of a meeting that Gray only called because of the allegations. Indeed, if someone were interested in a real, thorough investigation, it would have made more sense to engage whomever was doing the investigation and then schedule a meeting after a full investigation was completed and a report had been written. Calling a meeting first, then trying to shoehorn an investigation into the few days remaining, is the exact opposite of how you would expect this to be handled if someone wanted “a thorough investigation” as Depper claimed (14:15).

In fact, they even stated in the meeting that the investigation was not complete at the beginning of the meeting: 16:48 “This investigation is ongoing” (16:48), and “Unfortunately with the task that they had, they were unable to get it all done. What they did complete was their investigation into the Blue Hog Report. (17:18) Curiously, they ignored multiple articles we wrote (here, here, and here) after the initial article.4

Again, there was nothing requiring that the party have a meeting on August 17. Gray only called a meeting on that date after he caught wind that State Committee members were circulating a petition to call a special meeting under the DPA rules. Gray apparently wanted to get out in front of that potential call for a meeting, and the investigation/report was artificially retrofitted into that timeframe, which strikes me much more as damage control and public-relations spin than a true attempt to get to the bottom of anything.

Also on Page 1, the report states that the firm was “not asked to make recommendations on governance and management of DPA.” On page 12, however, the report recommends an independent outside audit (arguably a management issue) and improved record-keeping for financial reporting, which is certainly a management issue. So…which is it?

Most concerning on Page 1, however, is the statement that the law firm “met with Ms. Depper initially and other times.” Depper herself noted (starting at 13:30) that originally Michael John Gray asked her to investigate the allegations, but that some people were concerned that Depper might have a conflict, so Shults & Adams was contacted.

Think about that. You have a person who (a) is outside counsel for DPA, NOT a DPA employee who would seem to have any information relevant to allegations about how DPA was being run and reporting contributions and expenditures, and (b) stepped aside to let someone else do the investigation specifically because people thought she had a conflict of interest. Depper has only been DPA attorney since some time early in 2019, and her name does not appear as a signor or notary on any of the financial reports that formed the bulk of the allegations in our prior posts. In what world does it make sense for Shults & Adams to meet repeatedly (by their own admission) with someone who has no relevant first-hand information about the allegations and, more importantly, has a conflict that precluded her from handling the investigation in the first place? More accurately, what is the point of Depper stepping aside and letting Shults & Adams handle the “independent investigation” if Depper was then directly, repeatedly involved in that very investigation?

Page 2

The report again notes that they interviewed Annie Depper “at least once” without ever explaining why interviewing someone who had a conflict was proper. It also states on Page 2 that they interviewed Christina Mullinax, the “Data Director of DPA.” Why? Ms. Mullinax was hired in July 2019. There is no conceivable way that she could have information relevant to the allegations. More importantly, the prior data director, Misty Fox, did have information relevant to several of the allegations, and the report does not even say that the firm attempted to speak to her.5

Page 3

The report states that Shults & Adams tried to contact me to discuss the allegations. This did not happen. I would have been happy to provide additional information or, as you will see below, hold their hands through why they were wrong about everything related to Karyn Bradford-Coleman’s salary and her notarizing of certain DPA documents, but nobody asked me. Which is…whatever. But why say that you attempted to contact me?

Page 4

It is on Page 4 where the report starts to get into the actual substance of the various allegations. Noticeably, however, it starts off by failing to mention the name of the compliance company that allegedly created all of the problems. Michael John Gray stated in the meeting that “compliance is not done in the office” by DPA office staff, but in the same breath said there was “some deficiency on the staff in the office.” (33:30) This “deficiency” is never explored in the report.

The strangest part of Page 4, however, is this quote: “By late 2017, DPA staff and officers perceived problems with its former compliance company’s performance, including non-responsiveness to DPA communications, failure to respond to Federal Election Commission (“FEC”) inquiries, and failure to prepare and file required reports.” This is nonsensical for two reasons. First, all state and federal reports were timely filed in calendar year 2017, so “failure to prepare and file required reports” is either an outright lie or a perfect example of how little Gray and Bradford-Coleman understood about what was going on (and how much Shults & Adams took everything Gray, et al., said at face value). Second, the part about FEC inquiries ignores that, while responses to all of the five inquiries (Requests for Additional Information) from the FEC in 2017 were late, all five required input directly from DPA in order to respond. The report simply ignores DPA’s failure to provide information in a timely manner (or, alternatively, DPA’s failure to ensure that reports were timely filed).

Page 5

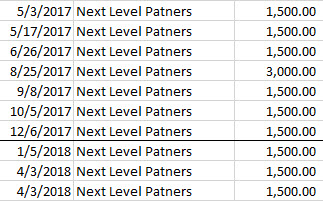

Oh, man. On Page 5, the report says that Karyn Bradford-Coleman tried to get in touch with the prior compliance company (Next Level Partners) in the days leading up to the April 16, 2018, deadline for the first-quarter report, but received no response. If one generously assumes the last two payments in this list brought them current through May with what they owed the company for prior work, by the time the beginning of April 2018 rolled around, they were at least 90 days behind on paying the compliance company. People tend to become non-responsive when you don’t pay them, which is probably why the April FEC report was filed on time, but contained no information.6

Despite the report having been due on April 16, Mr. Blair Schuman was first contacted by email about the problem on April 24, 2018. (Why Bradford-Coleman failed to contact anyone for eight days after the deadline is not explained in the report.) The report continues, “Because DPA did not hear from the predecessor compliance company, DPA or Mr. Schuman prepared and DPA filed a one-page 2018 Q1 report on April 24, 2018.” Mr. Schuman then “agreed to assist DPA in preparing an amended” report.

In short, in just a few sentences, the report states that DPA intentionally filed a report that, at the time of filing, they knew was incorrect. Otherwise, why would an amended report have been needed immediately afterward? Michael John Gray even said they intentionally filed a one-page report (33:05), which would have been done despite knowing that a one-page report was wholly insufficient. More importantly, if the report as filed on April 24 was a good-faith attempt to have the correct information–which is what is what Michael John Gray’s signature on that report literally stands for–why did the “one-page 2018 Q1 report” not contain a single support document showing where any of the listed totals came from? Why does the report not explain where DPA/Schulman got the data that was used to create that April 24 report in the first place? Additionally, purely from a logistical standpoint, how did Schuman, who was contacted for the first time on April 24, manage to analyze and compile all of the data for a report that would be filed that same day, when none of that data was apparently available in a form that could be submitted with that report?

Somewhat laughably, the report later says on Page 6 that the incorrect total on this first report was unintentional. They filed a report without any support for the totals listed, knowing that they would have to amend it to correct those totals and provide documentation. If a wild-ass guess about what the totals were counts as “unintentional,” why would anyone ever bother to make sure totals were correct before filing?

All of this matters, of course, because intentionally filing a quarterly report that you know to be false makes the verification, which is done under penalty of perjury, false by definition. No amount of “we do not find any evidence of any intentional misreporting” can overcome the fact that the report admits that the April 24, 2018 report was filed with the knowledge that the listed totals were incorrect.

Page 6

The report then gets into the allegations regarding the waiving of filing fees for certain 2018 candidates. For whatever reason, the report never says who the DPA employee was who made the decision to waive the filing fees for Kati McFarland or Stele James.

It then takes a strange turn, saying, “With respect to Ms. McFarland, Ms. Coleman said that she resisted but ultimately waived the filing fee.” Reading just this part, you might assume that Karyn Bradford-Coleman was the person who waived the fee. However, this does not match what was said during the meeting (38:50), where Gray referred to “a former employee, waiving the filing fees of those two candidates.”

The report’s reference to Bradford-Coleman saying that she “resisted but ultimately waived the filing fee” is also curious. The decision to waive these fees was made in March 2018. At that time, Bradford-Coleman was not Chief of Staff. She did not take over that position until January 2019. More importantly, neither Chief of Staff nor Bradford-Coleman’s prior position were ones where waiving a candidate’s filing fee would be up to her, and Gray did not suggest that she had any role in this decision. Gray went so far as to say that Bradford-Coleman “was not the senior person in the office at that time.” (1:02:15) So (a) why did she claim otherwise, (b) what is the real story, and (c) why doesn’t what Gray said at the meeting match what the report said about this?

Page 7

Remember how the point of this report was, in part, “to investigate, to the extent feasible in a few days” (Page 1)? While time might have been short, you would at least expect that the firm could have tried to resolve who was telling the truth when two different people they interviewed had conflicting stories, right? That seems like basic investigative work. Yet, on Page 7, the report states, “We received conflicting reports regarding who authorized the waiver and whether Mr. James was encouraged to pay back the waiver through fundraising efforts.” No further elaboration is given, and the report makes no effort to even explain why it wasn’t possible to determine which story was accurate.

The report also states that the second amended 2018 Q1 report “appears to have been prepared on May 29, 2018, but it was not filed until October 16, 2018.” For some reason, however, the report does not explain how they determined that the report “appeared to have been prepared on May 29,” which is information that is not found anywhere on the face of the report. Similarly, the report does not offer even the barest explanation as to why that report was not filed until October 16, 2018, despite the report’s (apparently) being authored on May 29 specifically in response to Mr. Schulman asking the Secretary of State’s office about reporting the waived fees. At best, you have the outside compliance company figuring out that the waived fees should be reported differently7 and authoring a new report for the DPA to reflect this, then the DPA simply failing to actually file that new report. And that’s the best-case scenario here. Yet this oversight is never explained, even slightly.

In the interest of full disclosure, the report does accurately explain and clarify what went on vis-a-vis Darrell Stephens’ reports.

Page 8

The report says that Karyn Bradford-Coleman electronically submitted a report provided to her by Schuman. This is outright false according to the Secretary of State’s office, who explained in response to a related question about this report, that this report was a “paper filing” that was not faxed or submitted electronically. (Indeed, if it had been submitted electronically, then the missing pages would not have been something the Secretary of State could correct on their end, as the pages would have been missing in the file the DPA electronically submitted. This was not the case.) Gray even said himself that the report, like all reports, was hand delivered to the Secretary of State’s Office (30:55).

I mention this discrepancy between the statement that the 2018 Q4 report was “submitted…electronically” and the fact that it was actually a paper filing as further demonstration as to how much Shults & Adams took DPA’s statements about what happened at face value, without so much as a scintilla of verification by, say, asking the Secretary of State’s office if a report was actually electronically filed as the DPA claimed or even asking Michael John Gray how the report was filed.

The Shults & Adams report continues, “We have not determined whether they should have discovered and corrected [that the report online was missing several pages] earlier.” Which means, at the very least, that the firm did not ask anyone they interviewed whether someone in the DPA is responsible for seeing whether the document uploaded by the Secretary of State matches what was submitted by the DPA. (At the absolute very least, shouldn’t someone be responsible for glancing at the uploaded report and making sure the number of pages online matches what was submitted? Is that too much to ask?)

Page 9

Here is where the whole Shults & Adams report goes from being somewhat about investigation/clarification and becomes pure, obvious, unadulterated spin and disingenuousness. More specifically, this is where the report begins to address the allegations about Karyn Bradford-Coleman.

While looking first at why the DPA was late paying an FEC fine, the report states, “Email communications reveal that Ms. Coleman believed that DPA had an extension to pay until April 2019.” These “email communications” are never elaborated upon. Yet, the report also notes, “Mr. Reiff stated that the FEC does not grant extensions.” Meaning that Bradford-Coleman’s “email communications” were NOT with the attorney who actually handled the negotiation with the FEC, and she never asked that attorney–who would have been the absolute best person to ask, since the FEC fine was specifically something he handled–whether the DPA actually had an extension to pay. Who did she ask? Why didn’t she ask the one person who knew the answer without question? The report never answers either of these questions.

During the August 17 meeting, Gray either attempted to mislead the audience about the nature of the FEC fines, or he truly demonstrated his ignorance for all to see, while explaining why DPA did not pursue the compliance company for damages, he said (48:45) it was his understanding the FEC fines were for violations not in filing but in actions taken. This is false, though he did say he did not have all the information.8 As is very clearly delineated on the FEC Audit Referrals, here for the 2013-2014 cycle and here for the 2015-2016 cycle, they were referred to the Office of General Counsel and fined for failing to provide proper supporting schedules and excessive, prohibited, and other impermissible contributions or transfers. The audits also found mathematical discrepancies, failure to properly itemize disbursements, and failure to properly itemize loans among other things.

You know, reporting errors.

Bradford-Coleman Salary

Shults & Adams then turned to the allegations about Karyn Bradford-Coleman’s salary increases, and, honestly, the lack of actual investigation becomes embarrassing at this point. The report says that Bradford-Coleman took a pay cut when moving from her prior job to her job with the DPA and that the raises she received were designed to get her salary back to what she had been earning. Fun fact: This is a demonstrable lie.

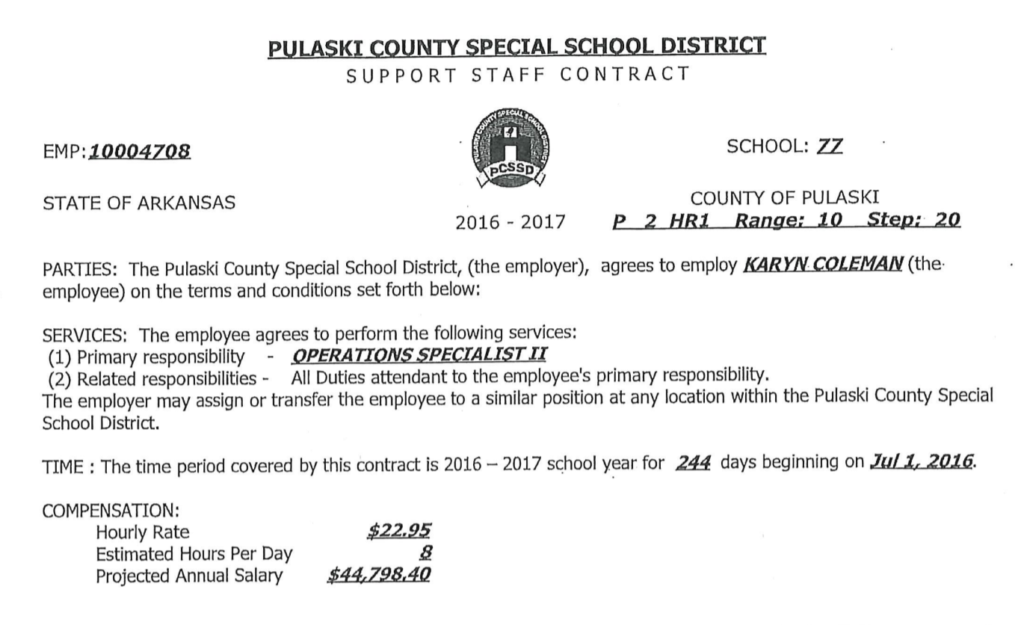

Prior to working at DPA, Karyn Bradford-Coleman worked for the Pulaski County Special School District. This means that her salary is public information that anyone could request and receive. I did so (see documents here); Shults & Adams did not. (We also confirmed with PCSSD that they had not received a request from Shults & Adams or anyone else for Bradford-Coleman’s personnel records during the period of this investigation.)

As shown above,9 Bradford-Coleman’s final salary at PCSSD was $44,798 per year. When she began at DPA in June 2017, according to Page 9 of the report, she was making $42,000. That is, of course, a slight pay cut…which was more than covered when she got a raise to $48,000 in October 2017. If the whole purpose was to get her salary back to what she was making, that should have been the end of the need for raises for quite a while. The report ignores this pesky fact, however, and acts like the additional raises were all related to increasing her salary to pre-DPA-employment levels.

According to the report, Bradford-Coleman’s raise schedule was the subject of a memorandum of understanding that “Ms. Coleman drafted, and Mr. Gray approved.” Of course, nothing in the report explains why Michael John Gray could override party rules about raises through a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with an employee. Worse still, according to two members of the Executive Committee, when specifically asked about the MOU during the August 17 Executive Committee, Gray–contrary to the Shults & Adams report–said that there was no actual document and that it was just conversations between him and Ms. Bradford-Coleman. If there was no MOU, someone lied to Shults & Adams and was never pressed on that lie or asked to produce the MOU; if there was an actual MOU, Gray lied to the Executive Committee rather than providing the document. Neither answer is acceptable.

Additionally, the MOU/scheduled raises story doesn’t hold water when you compare it to Bradford-Coleman’s actual raises. The report claims that she received a raise (originally promised in December) in October 2017 ($48,000), April 2018 ($51,000), and September 2018 ($56,600). Yet, according to the DPA’s own compliance reports, this is false. Bradford-Coleman received a raise in November 2017 that bumped her take-home pay from $1,451.85 per paycheck to $1,627.96. She received another raise (to $1,851.62 per paycheck) in December 2017.10 She received an additional raise moving her up to $2,203.56/paycheck in October 2018. The Shults & Adams report, in addition to being wrong about the months of some of the raises, completely omits the December 2017 raise that Bradford-Coleman received. And this is information that was publicly available, provided by the DPA in its quarterly reports.

If the “investigators” could not be bothered to check that the story about raises against information than anyone could obtain, and if they could not be bothered to see if the story about a paycut justifying the raises made any sense compared to the DPA’s own reports, how much faith can anyone put in the other conclusions they reached while relying upon statements from the DPA?

Page 10

The discussion of Bradford-Coleman’s salary information continued on page 10, where the report noted that the MOU between Bradford-Coleman and Gray said that she was to receive a raise in December 2017, but that Gray bumped the timing of that raise up to October 2017 when another DPA employee got a raise. Except…if the MOU said she was to get a raise in December, what would it matter if someone else got a raise at a different time? She should have received the raises as memorialized in the MOU. Otherwise, what is the point of the MOU in the first place if Gray could simply ignore it and do raises as he pleased?

Relatedly, the report reveals, without the least bit of analysis, that Gray’s excuses for not getting Executive Committee approval for raises were full-on ridiculous. Gray “stated that the Executive Committee meets quarterly, so he cannot wait for an Executive Committee meeting for every salary decision.” For one thing, just as was done in this case, the rules allow for Gray to call a special or emergency meeting of the Executive Committee outside of the regular quarterly meetings, so he was not limited to only the regular meetings. Additionally, even taking their report at face value for the sake of argument, Bradford-Coleman received raises in October 2017, April 2018, and September 2018. Two of Bradford-Coleman’s raises were the month after a quarter ended, which would have been the exact months that Executive Committee meetings were already scheduled. The third (September 2018) would have been the last month of the third quarter, so Gray could (and should) have at least brought up that raise at the Executive Committee meeting the next month. He did not, and his justification is one of the most disingenuous, deceitful things in the entire report. Shults & Adams took it as Gospel.

Further illustrating the lack of real investigation, Page 10 states that Shults & Adams were given Executive Committee meetings minutes from December 2018 and April 2019, but that prior minutes “were in the possession of the former DPA Secretary and were not readily available for review before the conclusion” of the investigation. Yet, at the August 17 meeting (26:05), Gray noted that the minutes had not been requested until the day before and would be given to the firm after the meeting. Seems like something someone might have asked to see well before the literal day the report was due to DPA under Gray’s needlessly abbreviated deadline for the report.

Page 11

During the meeting, Lottie Shackelford stood up and said that she “would like the record to reflect that Karyn Coleman has not done anything wrong based on this report.” (1:28:15) Rather than being proof of exoneration, however, this statement illustrates just how little real analysis was done for this investigation and report. And nowhere is that more evident than when Shults & Adams turned to the allegations about Bradford-Coleman’s improper notarization of DPA reports.

The report takes issue with the original assertion that using a stamp of Gray’s signature was akin to using a mark to sign rather than a real signature. It ignores, however, that this assertion in the original post was a quote from a former employee of the Secretary of State’s Office who had overseen the notary registration. Pinning that on BHR as something that we got wrong is pretty rich, considering Shults & Adams did not contact anyone at the Secretary of State’s Office for an opinion on this matter.

More importantly, even if we take Shults & Adams at face value on the notary issue, their own analysis demonstrates that Bradford-Coleman was improperly notarizing documents. According to the report, Gray “authorized Ms. Coleman to stamp his signature on any quarterly report on which it was stamped.” However, one of the cases cited by Shults & Adams on Page 11 states that the purpose of a notary “is to certify the identity of the person who executed the instrument.” By definition–and this is not debatable–the person who stamps a signature on a document is the “person who executed the instrument.” It does not matter if she stamped Gray’s name, her name, or “John Shaft” on the signature line; by stamping the document, even at Gray’s direction, Bradford-Coleman (not Gray) executed the instrument. And, as the Secretary of State’s Office explains, it is completely improper for a person to notarize a document that she executed.

Michael John Gray’s Disappearing Act

Not that we should take Shults & Adams at face value when it comes to the notary issues. In the report, they write, Gray “reported being present in the room when Ms. Coleman stamped and notarized his signature.” This is hard to believe, just as a matter of logic. If Gray was present in the room and had reviewed the report, why not just sign his own name? We’re talking about four signatures per year, not “many at one time” like the report suggests.

But we don’t have to limit ourselves just to the illogic of Gray’s assertion. Not when we have proof that he was not at DPA headquarters for at least two of the stamped signatures.

The 2017 4Q report was notarized on Monday, January 15, 2018. That was a snowy day, with most of the state having received snow overnight and more snow expected that day. According to a former DPA employee, Gray was out of the office that entire week, including January 15. This former employee was the one who locked up on Monday, January 15, and was the last person out of the office, so she was able to confirm that Gray was nowhere in sight that day. Moreover, Gray’s own social media for that day shows that he was in Augusta, playing in the snow with his son, well before sunset.11

Even without the former DPA employee’s recollection, are we really to believe that Gray drove to Little Rock on a snowy day just to review the report, then had Bradford-Coleman stamp his name on that report (instead of just signing it himself since he bothered to make that drive), watched her notarize it, and drove right back to Augusta? That’s a level of commitment to the job that Gray has literally never shown.

Additionally, the 2018 4Q report was due on January 16, 2019. Also scheduled that day was an introduction of new Democratic legislators at the Capitol, at which Gray was supposed to speak (what with being Chair of the party and all). Gray did not attend that event, however. Why? Because he was at the ground-breaking ceremony for the medical marijuana farm that his mother owns part of. You can even see him in pictures posted by KATV:

That Gray was not in the office at all on January 15, 2019, was also confirmed by two former DPA employees, both of whom noted that it was because he was at the marijuana farm event.

So, for at least two of the stamped signatures where Gray “reported being present in the room” for the notarization, we have visual proof that this was false, all of which was located in less than an hour on social media. Shults & Adams apparently could not be bothered to verify even the most basic assertions from Michael John Gray.

Conclusion

The Shults & Adams report was, by all accounts, incomplete. That is to be expected when someone is given only a few days and a limited scope to complete an investigation into numerous allegations.

However, based on what we’ve seen from the incomplete version of this report, there is little to suggest that a more complete version would be anything more than a fuller whitewashing over any errors or misdeeds by Michael John Gray and/or Karyn Bradford-Coleman. Perhaps this is unsurprising. Perhaps it was the entire point of the “investigation” all along. But it is absolutely worth keeping in mind as you see how the party handles the two grievances tomorrow and, moreover, as you think about whether the party is moving in the right direction under Gray.

Which they failed to properly call under the DPA rules, because of course they did.↩

If we’re not being charitable, the whole thing could accurately be described as a festering pile of bullshit designed to cover for Michael John Gray and Karyn Bradford-Coleman. But let’s stay charitable for now, ya know?↩

Interestingly, one of the reasons given by Depper (14:50) for choosing Shults & Adams was that they had experience in banking and financial regulation, yet…the report explicitly states that Shults & Adams “was not asked to…audit the books and records of DPA.” This is akin to saying you hired a coach because he had experience as an offensive coordinator, then telling people that he was not asked to have any role in the offensive planning. But I digress.↩

Perhaps even more curiously, despite assuring folks that a second, more complete report would be forthcoming, no such report has been provided to people who have asked for it.↩

At least six people listed on page 2 had Ms. Fox’s cell phone number.↩

That the April 2018 FEC was on time is never mentioned in the report when discussing the prior compliance company’s alleged failures.↩

Because no one at the DPA could be bothered to figure this out or know the rules, apparently?↩

WHY NOT?!?!↩

In publicly available documents that Shults & Adams didn’t bother to get.↩

Inexplicably, her pay briefly went down to $1,655.14 for 6 weeks in February and March, then went back up to $1,851.62 in the second half of March.↩

Sunset was 5:18pm that day in Augusta, AR, according to Google.↩