Depending on how you measure such things — specifically, whether you go by the time it really happened or by the time on the certificate of death — my dad passed away five years ago this coming Sunday or Monday. Personally, I use April 17 as the date, both because that’s when it really happened (so pretending like he was alive into April 18 seems weird to me) and because I see some kind of weird cosmic poetry in the idea that he passed on 4/17 and we spent the happiest years of our lives together in the 417 area code. Perhaps that a reach, but I don’t really care; sometimes you have to just hold on to whatever you can.

In the intervening five years, I have tried several of times to sit down and write something — anything — about him. An open letter, a eulogy, an anecdote about a specific memory, even just a bullet list of his good and bad traits. I have failed every time to get something on paper that is even remotely what I am trying to say.

Thinking about these failed attempts over the past weekend, I realized that writing about why I struggle to write about him might be more interesting (or at least more cathartic) than writing some elegiac words, especially when most of the people who will read those words never had the good fortune to meet my dad. So this is that effort, wherein I try to answer why writing about Doug Campbell has escaped me for so long.

…

My dad was just a few months shy of 26 years old when I was born. That has always struck me as an interesting age to have a kid in the 1970s — not old, but not exactly young, either. When I look at pictures of him with me as a baby, I see a weariness in his eyes that is somehow different from the kind of sleep-deprived weariness you see in most new parents. Not old, but not exactly young.

This kind of dichotomy is, I think, a big part of what makes it so hard for me to write about him, even five years on from his death. So much about him was “not X, but not quite Y.” That’s doubly true when you drill down to specific characteristics. For every good trait that I could focus on, there is a trait — not necessarily bad, but also not necessarily good — that I almost feel compelled to include, at least if I want to present a balanced picture. 1 So, if I tell you that he was, hands down, the greatest salesman that I have ever seen in any context, the voice in my head nags me to mention that, despite this talent and his ability to earn plenty of money with it, he was completely incapable of ever being comfortable with being comfortable and would almost always sabotage himself in some way.

Or if I tell you that he was a talented gambler and sleight-of-hand artist who provided for our family through much of the 80s and early 90s playing in illegal craps games around the country, something in me needs to mention that he inexplicably played only slot machines (a game where there is no advantage in being an experienced gambler) when he went to the casino.

Or maybe I mention how he loved my daughter — his first and only biological grandchild — with all of his heart. Of course, then I’d also have to mention that he only saw her a couple of dozen times, total, before he passed. (I don’t think I can explain the “why” here well enough to attempt it. At least not yet. It cuts through a part of my being that I’m just not ready to share. Maybe someday.)

Anyway, you get the picture. He contained multitudes. And multitudes can be hard to parse in a way that makes sense for anyone who did not experience them first-hand. So that is part of the problem when it comes to writing about him in an interesting or meaningful way.

…

Another difficulty in writing about him in any interesting, meaningful way is the guilt I feel. Not in his death, but in the fact that, at the time of his death, I had not spoken to him in almost a year. Worse, I had been telling myself almost daily for months that I should call him, but I never did. Life and a divorce and a million other bullshit excuses for not picking up the phone got in the way. Or, at the very least, I pretended like they got in the way. That’s something that I don’t know if I’ll ever totally be able to forgive myself for.

You see, while he and I were not quote-unquote estranged, there was some distance between us in his final years. We had settled into a routine that worked, to an extent anyway. I called him on Father’s Day and his birthday in August, and he called me on my birthday and Christmas. But we had played phone-tag on Christmas 2016, and neither of us followed up the following day. I guess we both assumed we would talk again some other time. It remains the worst assumption I have ever made. That’s something I know will haunt me forever.2

Whenever I mention this feeling of guilt to someone, the response is usually something about how it isn’t my fault. Logically, I know that it’s not my fault that he’s dead. But … that’s not the point, and that’s not where the guilt comes from. I don’t feel guilty because he’s gone; I feel guilty for not making more effort, for not making more of the time that he was here. I feel guilty for every minute that I could have spent with him but didn’t, for every call that I sent to voicemail because I was “busy.”

I feel guilty for even having to wonder if, in his final moments, he knew that I loved him unequivocally, flaws and all.

…

I need to share this story, because I still don’t know what to make of it, so I am going to include it right here for lack of a better option.

Almost exactly a year ago, I was perusing random old yearbooks on classmates.com for purposes of a goofy thread that I was doing on Twitter, showing high school photos of various Arkansas politicians. On a whim, I pulled up the yearbook from my dad’s senior year. I found his senior picture and again noticed how serious his eyes looked, even at 17.

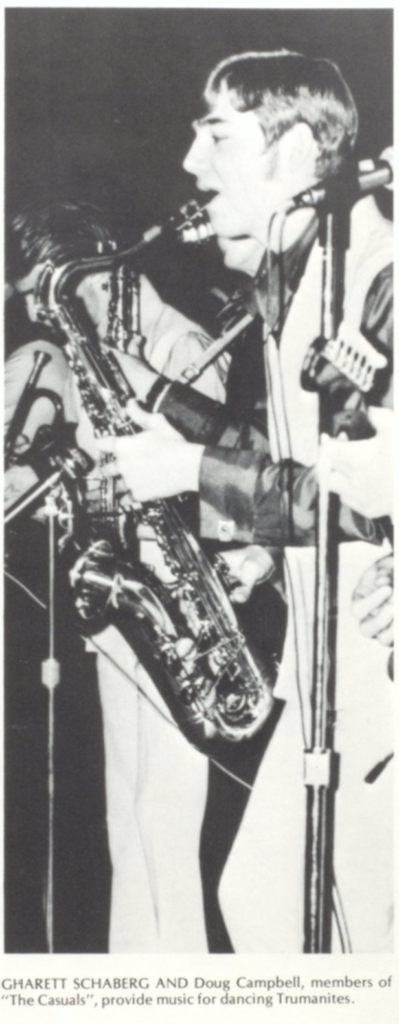

Flipping through that yearbook, however, I also saw this:

I saw his name in the caption and recognized the nose and hair and trumpet in the background. That was definitely my dad in a band called “The Casuals.” I had no idea he had ever been in a band! Even when I was in a band in high school, he never mentioned that he had been in one.

I called my brother and asked if he knew anything about this. He was as baffled as I was.

I called my mom, a woman who had known Doug since he was 21 or 22 and who had been married to him for 22 years, and asked if she knew anything about it. She had no clue.

So, after some digging around, I found contact information for a woman who runs a Facebook page with a lot of the 1970 senior class in it, and I asked her about it. She graciously answered me:

“I didn’t know your dad very well. I only had him in a class or two. The Casuals were a group of classmates that got together and played for events. We all went roller skating at B&D on the weekend and the rink would host a band and the Casuals would be one of them. We skated and danced almost every weekend.”

He had a great ear for music and was a very good trumpet and harmonica player, so that he was in a band wouldn’t have been surprising. He even talked about being in high school band a few times. But never once did he mention The Casuals to me, my brother, or my mom.

I still can’t wrap my head around it.

…

On the other hand, there are some things that I can say with complete certainty that I know about Doug Campbell.

I know that his favorite movies were the Friday trilogy and old Zatoichi samurai flicks.

I know that he was a very good baseball player who had no interest in watching baseball on TV as an adult, but who was keenly interested in updates on home run chases involving Mark McGwire/Sammy Sosa and later Barry Bonds.

I know that he was a bit of a neat freak and kept his own belongings perfectly organized, even during the times when things were falling apart around him.

I know that, if he had it all to do over again, he would probably make many of the same mistakes. I know I would forgive him for them again as well.

I know that he loved Christmas as much as any little kid you’ve ever met and would wake us up ridiculously early hours because he was so excited to see us open presents.

I know that he could have been wildly successful in a corporate sales situation. I also know he would have been miserable doing that and would have found a way to sabotage it.

I know that he would have absolutely adored Jess if he’d met her.

I know that he was literally so afraid to face the demons of his own childhood that he intentionally got himself arrested the night before his dad’s funeral. I know that there’s a part of me deep down that completely understands this, even if my childhood was infinitely better than his.

I know that the only two times I ever saw him cry were at his grandpa’s funeral and when my daughter was born.

I know that I have a number of his mannerisms, for better or worse.

But, above all else, I know he loved me and my brother and my daughter more than anything in the world, even if he was not always great about showing that love and would occasionally make terrible choices that impacted people he loved in bad-to-awful ways.

…

“Be good.” That’s how Doug signed off nearly every phone call with me. I never thought much about why he said “be good” rather than “bye” or whatever. To be honest, I still don’t know.

But I love that he did. It’s aspirational and positive and the kind of advice that is never going to get you in trouble.

I’d give everything I own to hear him say it one more time.

…

I could go on and on for hours. Hell, I could write a book about his career path alone. Car salesman, car dealership owner, professional illegal gambler, bar owner, owner of a tree-trimming company, and a few others I’m leaving out for now. But some of that needs to wait for a different time, either because I want to keep some details just for myself or because I am just not quite ready yet to dive into some things. Dealing with death is a process.

I had hoped that, in writing this, I might discover some Grand Truth that would explain why I hadn’t been able to write about him and reveal something deeper about myself or him or both of us. I suppose I got close on the first part: I’ve struggled to write about him because it’s just plain difficult to write about someone who has been, at various times, both your hero and your cautionary tale. It’s even harder when that someone passes in a way that leaves so many things unresolved.

As to the second part — the revelation of something deeper about one or both of us — I suppose this is as close as I can get right now: I hope I can be half the father that he was in his best moments, I hope I can be much better than he was in his worst moment, and I hope I can tell the difference between the two.

Be good.

Is it even possible for a child to present a balanced picture of their lifetime with a parent? I am positive that my version of this would differ wildly from my younger brother’s, despite sharing the same house and parents and most of the same experiences for long stretches of time.↩

Even I sit here typing this, I have tears rolling down my cheeks. I am incapable of thinking about a lot of this stuff without getting soul-crushingly sad. The sadness passes, and it is certainly less painful than it was five years ago, but it is yet another barrier to writing honestly about him.↩