Based on the amount of time I spent on Monday responding to people who were (apparently) appalled by the previous post about Judge Dan Kemp, it appears that we need to start this follow-up post by establishing a couple premises.

First up, Rule 1.2 of the Code of Judicial Conduct commands that “A judge shall act at all times in a manner that promotes public confidence in the independence, integrity, and impartiality of the judiciary, and shall avoid impropriety and the appearance of impropriety.” I put that last part in bold, because that’s what seemed to be missed by the myriad folks whose primary complaint was that I would suggest that there was something untoward in Judge Kemp’s actions and the contributions that followed when I did not have a smoking gun to irrefutably prove the allegations.

Thing is, if I had a smoking gun that I could use directly, the post would have been completely different, for reasons that should be obvious.1 What was important in the last post, however, was not some piece of concrete proof, but the appearance of impropriety which–at least in my opinion–seemed straightforward enough that I didn’t need to explain that aspect directly.

But let’s take a step backward for a moment and address two broader issues related to the previous post, albeit in different ways:

1. Judge Kemp had a duty to recuse, so he should have never been in the position to accept or reject the plea;

2. Judge Kemp’s statement in response to the previous post contained a knowingly false or misleading statement.

Judge Kemp’s Duty to Recuse.

In addition to the aforementioned Rule 1.2 (appearance of impropriety), we also have Rule 2.11(A), which states, “A judge shall disqualify himself or herself in any proceeding in which the judge’s impartiality might reasonably be questioned.” These rules are, generally, two sides of the same coin, since a judge whose impartiality might reasonably be questioned is not avoiding the appearance of impropriety, almost by definition.

While Rule 2.11 gives six specific examples where recusal would obviously be required, the Official Comments to Rule 2.11 make clear that those are not the only such scenarios, explaining:

[1] Under this Rule, a judge is disqualified whenever the judge’s impartiality might reasonably be questioned, regardless of whether any of the specific provisions of paragraphs (A)(1) through (6) apply.

[2] A judge’s obligation not to hear or decide matters in which disqualification is required applies regardless of whether a motion to disqualify is filed.

Accordingly, the measuring stick for where recusal is required–regardless of whether a litigant requests recusal–is simply where “the judge’s impartiality might reasonably be questioned.”

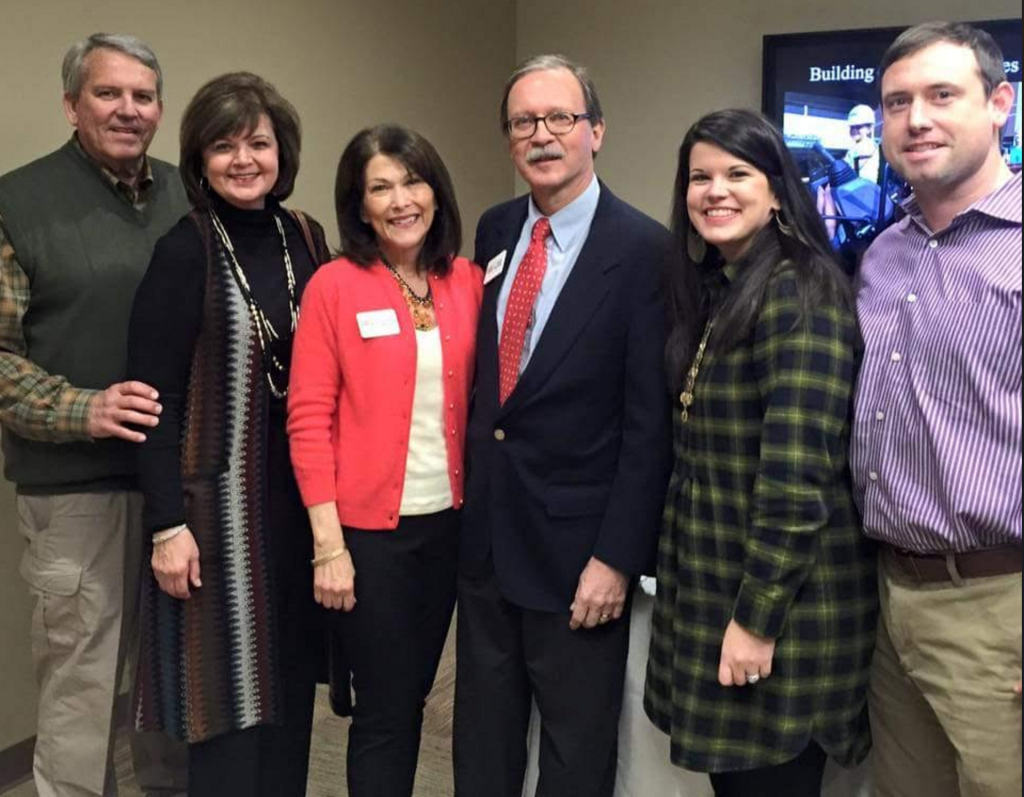

With that in mind, consider the factors at play in State of Arkansas v. Lea Ann Finn. The defendant in that case was the daughter of one of the judge’s oldest friends; Dan Kemp and Jim Hinkle have–in Hinkle’s words–known each other for their entire lives, and Judge Kemp and his wife remain good friends with the Hinkles:

L to R: Jim Hinkle, Kay Hinkle, Susan Kemp, Judge Dan Kemp, Katie Hinkle Henry, Shane Henry (picture via Judge Dan Kemp’s Facebook page)

Additionally, the defendant is the older sister of one of the judge’s daughters’ best friends.2 Erin Brogdon (Judge Kemp’s daughter) and Katie Hinkle Henry (Lea Ann Finn’s sister/Kay and Jim Hinkle’s daughter) have been friends for years and remain close friends to this day:

Henry (middle) and Brogdon (right), via Facebook.

Henry is second from the left; Brogdon is on the right (via Facebook)

In this scenario, the close relationships between the Kemps and Hinkles was more than sufficient to trigger reasonable questions about the judge’s impartiality in that matter. Indeed, that is exactly what was questioned in the prior post. More to the point, everything that followed after Judge Kemp’s failure to recuse, in spite of a duty to do so–including the plea agreement, contributions, and solicitation email–only serve to reinforce the idea that Kemp should not have been on the case in the first place.

Not that this analysis is purely speculation and opinion on my part. More than once, the Arkansas Judicial Discipline & Disability Commission has reprimanded and/or admonished judges for failing to recuse where their impartiality could reasonably be questioned. Where there is a duty to recuse because of questions of impartiality, the JDDC has made clear that this duty is absolute, writing:

While you have stated, and others have confirmed, that the defendant received no preferential treatment, your [failure to recuse] did not avoid the appearance of impropriety and promote public confidence in the Judiciary as required by Canon 1.2.

Unfortunately, at least based on the responses I received on Monday, I suspect that this analysis will fall on deaf ears and will be chalked up to my wanting to explain away my previous post. That’s false3, but it seems inevitable. So we might as well move on to the next point.

Knowingly False or Misleading Statements.

Also worth noting is Rule 4.1(A)(11), which mandates that a judicial candidate shall not “knowingly, or with reckless disregard for the truth, make any false or misleading statement.” This is bolstered by Rule 4.1(B), which requires a judicial candidate to take steps to prevent other people from doing anything that the judge himself would not be allowed to do under 4.1(A).

These Rules become relevant to our discussion when we turn to Judge Kemp’s response to Monday’s post:

In our judicial system it is the prosecutor, not the judge, that negotiates and recommends plea bargains. The plea agreement in the referenced case is no different than thousands of other cases that involve first time [sic] offenders in Arkansas. Furthermore, according to rules of professional conduct – which Judge Kemp has pledged to uphold – judicial candidates should, as much as possible, not be aware of those who have contributed to their campaign. Any accusation or suggestion that Judge Kemp arranged a favorable ruling in exchange for campaign support is categorically false, and reeks of dirty politics from his opponent’s campaign.

Even if we ignore the bland statements about how procedure is supposed to work and Kemp’s pledging to uphold rules of professional conduct, there’s another problem with the statement. Namely, it states that Ms. Finn’s case was “no different than thousands of other cases that involve first[-]time offenders.” It could literally say that she was treated no differently than other unicorns and it would be no less nonsensical, because Ms. Finn was not a first-time offender. Not even close.

You see, back in 2006, Ms. Finn (whose surname at the time was Walker) was arrested in Faulkner County and charged with Y-felony manufacture/possession/distribution of less than 28g of methamphetamine, B-felony manufacture/possession with intent to distribute counterfeit methamphetamine, C-felony possession/use of drug paraphernalia, DWI-1st (misdemeanor), refusal to submit to a chemical test, and careless and prohibited driving.

On May 15, 2007, Ms. Finn entered a guilty plea on all of those charges, and Judge Mike Maggio imposed a sentence of five years’ probation, $2,950 in fines and costs, and 80 hours of community service.

On July 6, 2007, Ms. Finn was charged with DWI and driving on a DWI-suspended license in Hot Spring County. On August 28, 2007, again in Hot Spring County, she was charged with DWI-2nd, driving on a DWI-suspended license, careless drive, and not wearing a seatbelt. The two Hot Spring County cases were tried at the same time on June 26, 2008, at which time the driving-on-suspended charges, as well as the careless and seatbelt charges were dismissed. The court also entered a docket notation to amend the DWI-2nd to DWI-1st because, according to the court, the Faulkner Co. DWI charge had not been recorded as guilty.

Prior to the trials on the Hot Spring County charges, the Circuit Court of Faulkner County issued a bench warrant was issued for Ms. Finn on June 9, 2008, and a petition to revoke her probation was filed with the Court. On June 10, a request was made to recall that warrant, and the request was granted with the docket notation that “Alternative Sanctions Were Taken.”

On June 1, 2010, Judge David Reynolds signed an order releasing Ms. Finn from probation.4

Knowledge.

Obviously, then, Ms. Finn was not a first-time drug offender, contrary to Judge Kemp’s statement on Monday. The only questions are whether Judge Kemp knew about Ms. Finn’s earlier guilty plea (a) at the time that the plea was entered and/or (b) at the time that the statement was issued on his behalf on Monday.

Yesterday, a person close to the situation, who asked to remain anonymous for purposes of this post, said Judge Kemp and Jim Hinkle “are good friends…going way back,” which fits with what Hinkle’s email said. When asked about Ms. Finn’s earlier charges and whether the judge was aware, this person said, “He knew she wasn’t a first-time drug offender or DWI[;] he knew better than that.”

This knowledge is important for two reasons. First, it makes Judge Kemp’s statement on Monday “knowingly false or misleading,” in violation of Rule 4.1(A)(11), as discussed above.

Secondly, such knowledge is relevant in the context of Judge Kemp’s assertion that the prosecutor and defense are the ones who negotiate and recommend a plea. That’s accurate on its face, but it glosses over the important next step under Arkansas Rule of Criminal Procedure 25.3, which delineates the responsibilities of a judge in plea agreements.

Specifically, for a plea of guilty in exchange for reduction or dismissal of other charges, the parties either need to seek the judge’s approval of the agreement ahead of time and make sure that the judge approves of the plea agreement OR, if no permission/approval is requested by the parties prior to presenting the plea to the court, the judge “shall advise the defendant in open court at the time the agreement is stated that: (i) the agreement is not binding on the court; and (ii) if the defendant pleads guilty or nolo contendere the disposition may be different from that contemplated by the agreement.”

Which is to say, if the judge was not asked for his approval of the plea agreement prior to presenting it to the court, which appears to be what Judge Kemp’s statement is suggesting, then Judge Kemp was required to tell Ms. Finn that the agreement was not binding on the court and that she could be sentenced to something other than the agreed-upon penalty.

At that point, we have two problems, which again go back to the idea of recusal and impartiality and integrity of the judiciary.

If Judge Kemp had personal knowledge of the prior drug and DWI convictions, but that information was not factored into the plea agreement as presented by the prosecutor, accepting the plea as recommended by the State means that Judge Kemp was not upholding the impartiality or integrity of the judiciary, since he knew that the underlying facts as presented were incorrect, yet he approved that plea agreement anyway. On the other hand, Judge Kemp risked possible censure by the JDDC if, in that situation, he had directed the prosecutor or defense to locate and provide the additional criminal history information before he would consider the plea. Thus, again, the only acceptable way to resolve this conundrum would have been to recuse (which, as noted, he should have done in the first place anyway).

Taking it a step further, and bringing this full circle for the time being, Judge Kemp’s acceptance of the plea agreement as presented, despite his knowledge of Ms. Finn’s past criminal history, makes the receipt of campaign contributions from Ms. Finn’s family two weeks later look questionable. And that is what the concepts of “the appearance of impropriety” and promoting “public confidence in the independence, integrity, and impartiality of the judiciary” are specifically designed to avoid.

TL;DR.

Ultimately, this post and the previous post about Judge Kemp boil down to three assertions:

- Due to his close personal relationships with the Hinkle family, Judge Kemp should have recused from Ms. Finn’s case at the outset.

- Judge Kemp’s personal relationships with the Hinkle family and his knowledge of Ms. Finn’s criminal history give his acceptance of the plea agreement and the subsequent receipt of campaign contributions the appearance of impropriety.

- Judge Kemp’s statement on Monday about Ms. Finn’s being treated list a first-time offender was knowingly false or misleading on its face.

As with anything, you, the reader, are free to accept or reject any or all of these assertions. If you reject them, however, I hope that you will at least be honest with yourself about why you’re doing so.

The post would not have been a post about whether the timing of the plea, contributions, and solicitation email appeared to be improper; it would have been a post about the evidence and potential judicial and criminal sanctions.↩

There is a rumor going around that Kemp’s daughter and Hinkle’s daughter were roommates at one point, but that is so far unverified.↩

And it demonstrates an ongoing, troubling willingness of those who support Kemp (or oppose Goodson) to ignore something that violates the very ethical standards that Kemp crows about following.↩

Curiously, the order releasing Ms. Finn from probation stated, “the Defendant has demonstrated to the Court that she has fulfilled the purposes of probation/S.I.S. by being a law abiding citizen during the time of his [sic] Probation.”↩